Absolute vs Relative Risk Calculator

How to Use This Calculator

Enter the control group risk and treatment group risk to see how absolute and relative risks differ. For example, if 10% of patients experience side effects without treatment and 7% with treatment:

Control Event Rate (CER): 10%

Experimental Event Rate (EER): 7%

ARR = 10% - 7% = 3 percentage points

RRR = (10% - 7%) / 10% = 30%

NNT = 1 / 0.03 ≈ 33 patients

Absolute Risk Reduction (ARR)

Absolute difference in risk between groupsRelative Risk Reduction (RRR)

How much the risk is reduced compared to controlNumber Needed to Treat (NNT)

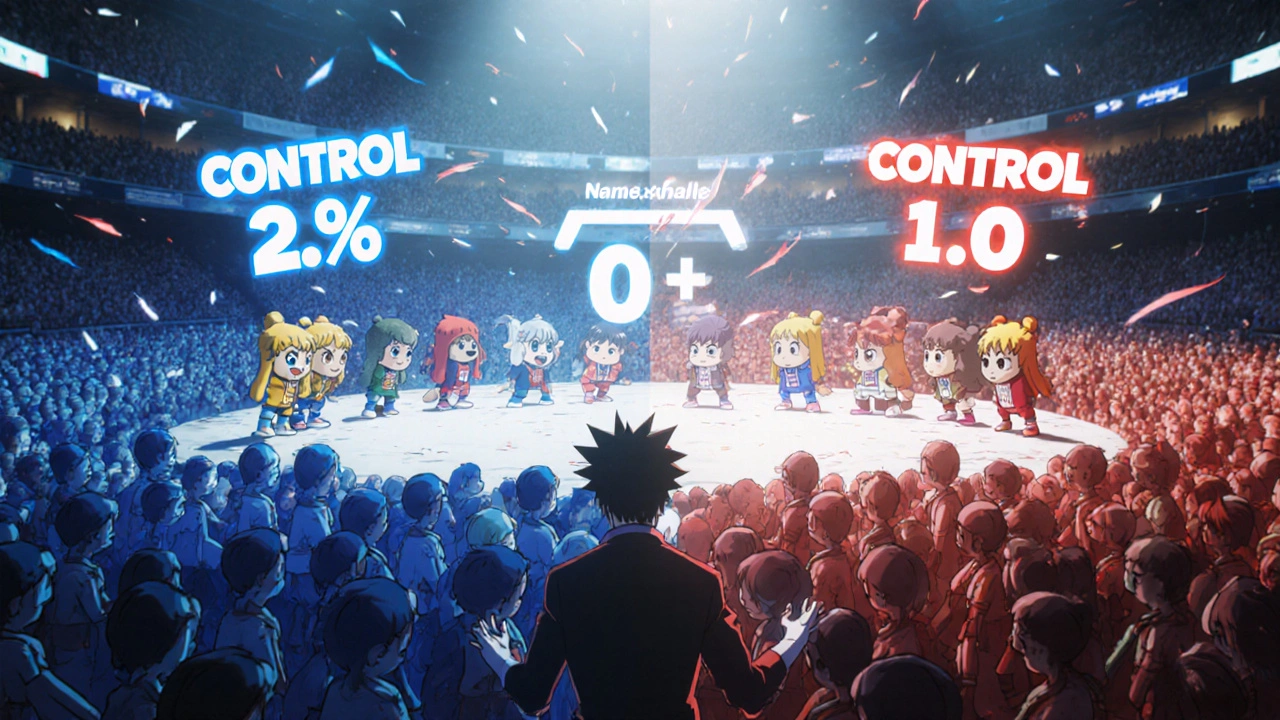

How many patients need treatment to prevent one adverse eventVisualizing a group of 100 patients:

Key: ● = Prevention of side effect (benefit) ● = Side effect (harm) ● = No effect

Interpreting Results

Always consider both absolute and relative risk:

- Relative risk reduction can make small benefits seem dramatic (e.g., 30% reduction sounds bigger than 3 percentage points)

- A large relative risk reduction with a low baseline risk means the absolute benefit is small

- The Number Needed to Treat (NNT) shows how many people need treatment to benefit one patient

When a new medication hits the market, headlines often shout about a "50% reduction in heart attacks" or a "90% cut in side‑effects." Those numbers sound impressive, but without context they can mislead patients and even doctors. The key to decoding those headlines is understanding the difference between absolute risk vs relative risk. This guide walks you through the two concepts, shows how they’re calculated, and gives real‑world examples you can use in a clinic or a conversation with a friend.

What Is Absolute Risk?

Absolute risk is the actual probability that an event (like a side‑effect) will happen in a specific group of people. It’s expressed as a percentage, a proportion, or a rate per 1,000 or 100,000 patients. For example, if 2 out of 1,000 patients taking Drug X develop nausea, the absolute risk of nausea is 0.2% (2/1,000).

Absolute risk answers the question, "How likely am I to experience this outcome?" It’s the number that patients care about when deciding whether to start a therapy.

What Is Relative Risk?

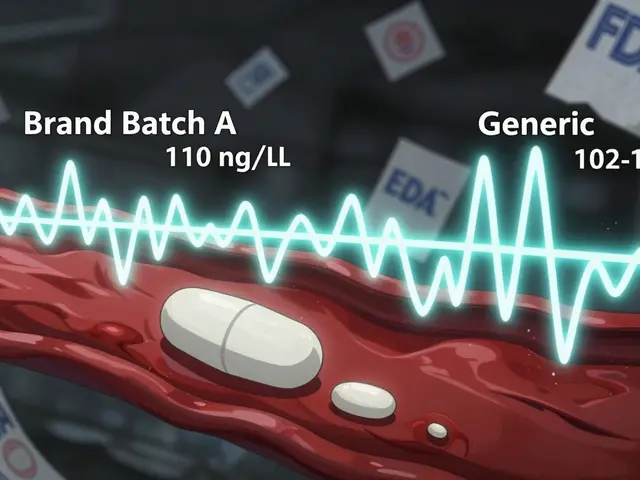

Relative risk compares the probability of an event in two groups - usually a treatment group versus a control or placebo group. It’s a ratio, not a raw percentage. If the same Drug X causes nausea in 2 out of 1,000 patients (0.2%) while the placebo causes it in 1 out of 1,000 (0.1%), the relative risk is 2.0 (0.2% ÷ 0.1%). This means the drug‑treated group is twice as likely to get nausea as the control group.

Relative risk is useful for researchers because it standardizes effects across different baseline risks, but it can sound dramatic when the underlying absolute numbers are tiny.

How to Calculate the Core Numbers

- Absolute Risk (AR): AR = (Number with event ÷ Total exposed) × 100%

- Relative Risk (RR): RR = Risk in treatment group ÷ Risk in control group

- Absolute Risk Reduction (ARR): ARR = Control Event Rate (CER) - Experimental Event Rate (EER)

- Relative Risk Reduction (RRR): RRR = (CER - EER) ÷ CER = 1 - RR

- Number Needed to Treat (NNT): NNT = 1 ÷ ARR (expressed as a decimal)

These formulas appear in CONSORT guidelines for reporting randomized trials and are required by regulators like the FDA and EMA.

Interpreting Numbers in Drug Side‑Effect Data

Imagine a new antihistamine reports a 30% relative risk reduction for drowsiness. The study says the control group had a 10% drowsiness rate, while the drug group had 7%. Here’s the breakdown:

- Control Event Rate (CER) = 10% (0.10)

- Experimental Event Rate (EER) = 7% (0.07)

- ARR = 0.10 - 0.07 = 0.03, or 3 percentage points

- RRR = (0.10 - 0.07) ÷ 0.10 = 0.30, or 30%

- NNT = 1 ÷ 0.03 ≈ 33 patients

The headline "30% reduction in drowsiness" sounds big, but the absolute benefit is only 3 out of 100 patients. If a patient is sensitive to drowsiness, knowing the NNT of 33 helps decide whether the trade‑off (cost, other side‑effects) is worth it.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

- Skipping the baseline: Reporting only RRR without the control risk hides how rare the event is. A 90% RRR is meaningless if the baseline risk is 0.001%.

- Using the wrong denominator: Some ads compare the treated group’s risk to the overall population instead of the proper control group, inflating the relative figure.

- Omitting time frames: Risks can change over months or years. Stating "50% lower risk" without saying "over five years" leads to confusion.

- Neglecting visual aids: Pictograms showing 100 icons (where shaded icons represent events) dramatically improve patient comprehension, as shown in a 2016 Cochrane Review.

When you present both ARR and RRR, start with the absolute number. Dr. Steve Woloshin and Dr. Lisa Schwartz recommend phrasing it like, "In the trial, 1 out of 100 patients on the drug had the side‑effect, compared with 2 out of 100 on placebo (a 50% relative reduction)." This order prevents the brain from over‑valuing the relative figure.

Communicating Risks to Patients

Effective communication blends numbers with plain language:

- State the absolute risk first: "If you take this medication, 1 in 100 people experience nausea. Without the medication, 2 in 100 experience it."

- Follow with the relative figure: "That’s a 50% relative reduction."

- Give the NNT when appropriate: "You would need to treat 100 people for one person to avoid nausea."

- Use visual tools: risk ladders, icon arrays, or short video clips.

Studies show that patients who see both numbers and a simple graphic are up to three times more likely to make an informed choice.

Practical Examples Across Therapeutic Areas

| Drug | Side‑Effect | Control Risk (CER) | Treated Risk (EER) | ARR | RRR | NNT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statin A | Muscle pain | 4% | 2% | 2 percentage points | 50% | 50 |

| Antidepressant B | Sexual dysfunction | 8.3% | 20.0% | 11.7 percentage points | −141% (increase) | ‑9 (Number Needed to Harm) |

| Chemo C | Neutropenia | 15% | 5% | 10 percentage points | 66.7% | 10 |

Notice how the relative reduction looks large for muscle pain (50%) but the absolute benefit is only 2 percentage points. For sexual dysfunction, the relative figure is misleadingly high because the drug actually raises risk.

Quick Checklist for Clinicians and Health Writers

- Always report both absolute risk and relative risk.

- Include the control event rate so readers can gauge baseline risk.

- Show ARR and calculate NNT (or NNH for harms).

- State the time horizon (e.g., "over 2 years").

- Pair numbers with a simple visual (icon array or risk ladder).

- Use plain language - avoid "relative risk reduction" jargon; say "percent less likely" instead.

Following this checklist reduces the chance of statistical deception and helps patients make choices that match their values.

Future Outlook

Regulators are tightening rules. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance now expects direct‑to‑consumer ads to present both absolute and relative metrics side by side. The European Medicines Agency already requires that patient information leaflets contain absolute risk numbers. By 2025, more than 90% of clinical trial registries are projected to require both metrics, which should gradually raise the overall literacy of risk among clinicians and the public.

What’s the biggest mistake people make when they hear "50% reduction"?

They assume their personal risk drops by half, forgetting that the baseline risk might be very low. For example, a 50% drop from 0.2% to 0.1% is barely noticeable for most patients.

How do I convert a relative risk reduction into an absolute risk reduction?

Multiply the relative risk reduction by the control event rate. ARR = RRR × CER. If the control risk is 10% and the RRR is 30%, the ARR is 3%.

When should I use Number Needed to Treat (NNT) instead of ARR?

NNT translates ARR into a count of patients, which is easier for non‑medical audiences. An ARR of 5% equals an NNT of 20, meaning you need to treat 20 people for one to benefit.

Do regulatory agencies require both absolute and relative figures?

In the U.S., the FDA’s draft guidance (2023) urges inclusion of both; the EMA already mandates it. Compliance varies, but most major journals now ask authors to report both metrics.

Can visual aids really improve patient understanding?

Yes. A 2016 Cochrane Review found that risk ladders and icon arrays increased accurate risk interpretation by up to 45% compared with text alone.

kevin burton

October 25, 2025 AT 12:26Understanding the difference between absolute risk and relative risk is essential for anyone interpreting drug safety data.

Absolute risk tells you the real chance that a particular side‑effect will happen in a defined group of patients.

It is usually expressed as a percentage, a proportion, or a rate per 1,000 individuals.

For example, if two out of a thousand patients experience nausea, the absolute risk is 0.2 %.

Relative risk, on the other hand, compares that chance to a control group and is presented as a ratio.

If the control group has a 0.1 % chance of nausea, the relative risk of the drug is 2.0, meaning the drug‑treated group is twice as likely to get nausea.

The headline “50 % reduction in heart attacks” sounds dramatic, but without the baseline risk it can be misleading.

A 50 % reduction from 0.2 % to 0.1 % is a tiny absolute benefit for most patients.

Clinical guidelines therefore recommend reporting both absolute risk reduction (ARR) and relative risk reduction (RRR).

ARR is simply the difference between the control event rate and the experimental event rate.

RRR is the proportion of that difference relative to the control risk, often written as a percentage.

The number needed to treat (NNT) translates ARR into a count of patients who need the therapy for one to benefit.

An ARR of 3 % corresponds to an NNT of about 33, which helps clinicians weigh benefits against costs and side‑effects.

Visual aids such as icon arrays or risk ladders have been shown to improve patient comprehension dramatically.

By presenting both absolute and relative numbers side by side, doctors can avoid statistical deception and patients can make choices that match their values.

Deborah Galloway

October 25, 2025 AT 13:33It can feel overwhelming when you see a headline like “90 % reduction” and wonder what it means for you.

Remember that the absolute chance of the side‑effect might be very low to begin with, so the real benefit could be modest.

Putting the absolute risk first helps patients see the true magnitude, and then the relative figure adds context.

I always try to phrase it as “1 out of 100 people experienced nausea with the drug, compared with 2 out of 100 without it.”

This simple framing keeps the conversation clear and reassuring.

Charlie Stillwell

October 25, 2025 AT 14:40Your jargon‑laden rant about relative risk is as empty as a placebo bottle 😂.

Ken Dany Poquiz Bocanegra

October 25, 2025 AT 15:46Relative risk gives a quick sense of direction, but absolute risk grounds the decision in reality.

A 30 % relative drop looks impressive until you see the baseline is 10 %, yielding an absolute reduction of only three points.

Keep both figures handy.

Tamara Schäfer

October 25, 2025 AT 16:53i think the most ccritical point is to never skip the baseline risk, otherwise the reltive numbers can mislead.

also, time frame matters – 50% lower risk over one month is not the same as over five years.

visual aids like icon arrays really help patients grasp the numbers.

these simple tools make the stats feel less scary.

Tamara Tioran-Harrison

October 25, 2025 AT 18:00Indeed, the omission of baseline data is a classic example of statistical obfuscation, isn’t it?

One might argue that such practices elevate marketing above science, a notion most certainly commendable.

:)

Max Lilleyman

October 25, 2025 AT 19:06Great rundown on absolute vs. relative risk! 👍📊

Buddy Bryan

October 25, 2025 AT 20:13Your summary captures the essential formulas, but let’s add a practical tip: always calculate the number needed to harm (NNH) when a drug increases risk, as with the antidepressant example.

Reporting NNH alongside NNT gives clinicians a balanced view of benefits versus harms.

Also, remember to state the follow‑up period; a 30 % relative reduction over six months is not comparable to the same reduction over five years.

When communicating to patients, pair the numbers with a simple icon array – research shows this boosts understanding by up to 45 %.

Finally, be transparent about any conflicts of interest in the study design.

These steps ensure trust and clearer decision‑making.

Jonah O

October 25, 2025 AT 21:20Some might tell you the FDA just wants clean numbers, but have you considered that the agencies could be pressured by pharma lobbyists to hide the true baseline risks?

If the real absolute risk is suppressed, the relative figures become a tool for manipulation.

It’s worth questioning who benefits from the headline hype.

Stay vigilant.

Aaron Kuan

October 25, 2025 AT 22:26Risk math is a kaleidoscope of colors, not just cold stats 🌈

Benjamin Sequeira benavente

October 25, 2025 AT 23:33Let’s turn these stats into action!

Knowing the NNT empowers you to choose wisely and advocate for your health.

Share the numbers with your doctor, ask for visual aids, and never settle for vague percentages.

Together we can demystify risk and make better decisions.