Imagine you need an EpiPen. Your doctor prescribes it, your insurance approves it, and you head to the pharmacy. But instead of the brand-name auto-injector, you get a generic epinephrine vial and a separate generic injector. You’re told they’re the same. But when you try to use them together, the injector doesn’t click right. The needle doesn’t deploy. You panic. This isn’t a hypothetical. It’s happening to thousands of patients every year.

The problem? A branded combination product - like an EpiPen - isn’t just a drug. It’s a drug + a device, designed and tested as one unit. When generics enter the picture, regulators and pharmacies treat them like separate pieces. But they don’t work that way in real life. That’s the core issue with generic combination products: when multiple generics equal one brand, the system breaks.

What exactly is a combination product?

A combination product is anything that combines two or more types of medical components - like a drug and a device - into a single therapeutic solution. Think prefilled syringes, inhalers with built-in dose counters, insulin pens, or auto-injectors like EpiPens. These aren’t just packaged together. They’re engineered to work as one. The drug’s effectiveness depends on how the device delivers it. A poorly designed injector can mean the difference between life and death.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has a specific definition: a product where components are physically combined, packaged together, or labeled for use together. The FDA assigns each combination product a Primary Mode of Action (PMOA). That’s the main reason it works. If the drug does the heavy lifting, the FDA’s drug center (CDER) reviews it. If the device is the star - like in an auto-injector - the device center (CDRH) takes the lead. This matters because it determines the approval path, the testing requirements, and who signs off on safety.

Why can’t you just swap out the drug and keep the device?

Here’s where things get messy. Traditional generic substitution laws were built for single-component drugs. If a brand-name pill has a generic version, pharmacists can swap them automatically - unless the doctor says no. It’s simple. Safe. Legal.

But with combination products, that rule falls apart. Take the EpiPen. The brand-name version has a specific auto-injector designed for the exact concentration and volume of epinephrine. A generic version might have the same drug - but a different injector. Even if both injectors are FDA-approved, they’re not interchangeable. The trigger force, needle depth, spring tension, and even the grip design can vary. That’s not a minor difference. It’s a safety risk.

The FDA’s Office of Generic Drugs says it clearly: you can’t assume a generic drug plus a generic device equals the branded combination. Each combination product must be tested as a whole. That means the generic manufacturer must prove their version performs identically to the original - not just the drug, but the entire system. This includes human factors testing: real people using the device under real conditions. If users can’t operate it correctly, it fails.

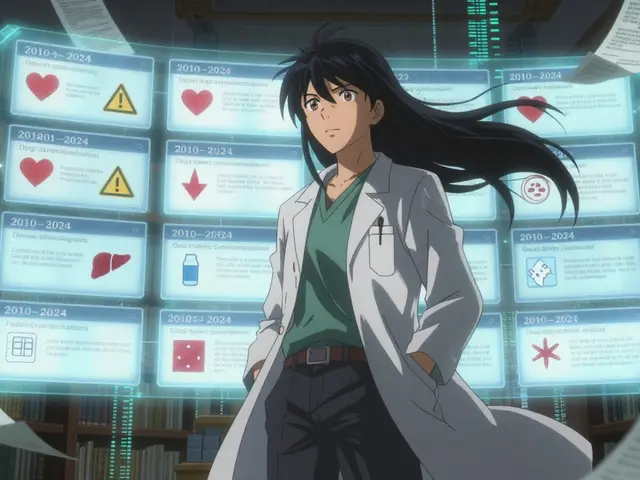

The hidden cost of complexity

Developing a generic combination product isn’t like making a generic pill. It’s like reverse-engineering a Swiss watch. The FDA requires detailed comparisons of the device’s user interface - button placement, tactile feedback, visual cues, even the sound it makes when activated. This isn’t just paperwork. It takes 18 to 24 months longer than a standard generic. And it costs $2.1 million to $3.7 million more.

That’s why only 17 companies control 83% of approved generic combination products. Most small generic manufacturers can’t afford the risk. The result? Less competition. Higher prices. Fewer options.

While over 90% of single-drug generics are available, only 12% of combination products have generic alternatives. And even then, only 38% of complex combination products have more than one generic approved. Compare that to 72% for regular generics. That’s not a gap. That’s a chasm.

What happens when patients get the wrong combo?

Patients aren’t just confused - they’re endangered. A 2024 survey by the National Community Pharmacists Association found that 68% of pharmacists have seen patients given mismatched components. One in five patients reported getting the wrong device with their generic drug. Some ended up with a vial of epinephrine and no injector. Others got a generic injector that didn’t fit their prescription.

On Reddit, a thread titled “Why can’t my generic EpiPen substitute normally?” had over 280 comments. One pharmacist wrote: “The auto-injector device is considered part of the product. So even if you have a generic epinephrine, you need the specific generic auto-injector approved for substitution - which often doesn’t exist yet.”

Patients are paying more, too. Those who get a branded combination product pay 37% more out-of-pocket than those on standard generics. And delays are common. Doctors report treatment delays of over three business days on average because of substitution confusion. In 2023, patient advocacy groups documented 217 cases where people couldn’t access a therapeutic equivalent - up 29% from the year before.

Why isn’t the system fixing itself?

The FDA knows this is a problem. In 2024, they released new guidance on how to submit comparative analyses for generic combination products. They’ve added 32 new reviewers to their team. And they’ve launched the Complex Generic Initiative 2.0, aiming to cut approval times by 30% by 2026.

But guidance doesn’t change practice overnight. The system is still built for single-component products. State laws haven’t caught up. Most states still allow pharmacists to substitute generics based on outdated rules. California and Massachusetts are leading the charge with new laws requiring pharmacists to verify that both drug and device components are approved as a pair. But 48 states still don’t have clear rules.

Even when a generic combination product is approved, pharmacies often don’t stock it. Why? Because it’s expensive. Because they don’t know how to explain it to patients. Because the manufacturer doesn’t push it. The supply chain isn’t designed for these products.

What’s the real solution?

The answer isn’t more paperwork. It’s better rules. We need a new category of substitution: “therapeutic equivalence for combination products.” That means if a generic version is approved as a complete unit - drug + device - it should be substitutable. Not just the drug. Not just the device. The whole thing.

Doctors need training. Pharmacists need clear protocols. Patients need to know what they’re getting. And regulators need to treat combination products as what they are: single therapeutic units, not two separate items.

Right now, we’re treating a heart pacemaker like a battery and a circuit board. We can replace the battery - but if the circuit doesn’t match, the device fails. We wouldn’t do that with a car. Why do it with medicine?

What patients and providers can do now

- Check the label: If you’re prescribed a combination product, make sure the pharmacy gives you the exact branded or approved generic version - not a mix-and-match. Ask: “Is this the full approved combination?”

- Ask for the product code: Every approved combination product has a unique identifier. Ask your pharmacist for it. If they don’t know what you mean, they might not be aware of the issue.

- Speak up: If you get the wrong components, report it. Contact your pharmacist, your doctor, and your state board of pharmacy. Your voice pushes change.

- Don’t assume substitution is safe: Just because something is labeled “generic” doesn’t mean it’s interchangeable. For combination products, it rarely is.

The future of combination products is growing fast. The global market is projected to hit $214 billion by 2028. But if we don’t fix the substitution system, patients will keep paying more, waiting longer, and risking harm. The technology is there. The science is there. What’s missing is the system that lets it work for the people who need it.

Can a generic drug be substituted for a branded combination product if the device is still branded?

No. Even if the drug component is generic and identical, the device is part of the approved product. Substituting a branded device with a generic drug (or vice versa) is not considered therapeutic equivalent by the FDA. The entire combination must be tested and approved as one unit. Using mismatched components can lead to improper dosing or device failure.

Why are there so few generic combination products on the market?

Because they’re extremely hard and expensive to develop. Manufacturers must prove the entire system - drug and device - works the same as the original. This requires human factors testing, comparative device analysis, and years of development. Costs can exceed $3 million, and approval takes 18-24 months longer than a standard generic. Most companies avoid the risk.

Do pharmacists know how to handle generic combination products?

Many don’t. A 2024 survey found 68% of pharmacists have encountered confusion with combination product substitutions. State laws haven’t kept up, and training is inconsistent. Pharmacists often rely on outdated substitution rules meant for single-drug generics. Patients should always ask: “Is this the full approved combination?”

Are there any generic combination products approved in the U.S.?

Yes, but they’re rare. Only 12% of combination products have generic versions. Some approved examples include generic versions of Adrenaclick (epinephrine auto-injector) and certain inhalers like Combivent Respimat. However, even when approved, multiple generics for the same product are uncommon - only 38% of complex combination products have more than one generic on the market.

How can I tell if my medication is a combination product?

Look at the packaging and prescription label. If it includes a device - like a pen, injector, inhaler, or prefilled syringe - it’s likely a combination product. Ask your doctor or pharmacist: “Is this a drug-device combination?” You can also check the FDA’s Orange Book or contact the manufacturer directly. If the product requires a specific device to work, treat it as a single unit.

Linda Rosie

November 22, 2025 AT 23:10Just got my generic epinephrine vial yesterday. No injector. Called the pharmacy. They said, 'Oh, we don't stock the device yet.' I had to drive 20 miles to another location. This isn't convenience-it's dangerous.

Vivian C Martinez

November 23, 2025 AT 10:03I work in a community pharmacy and see this every week. Patients are confused, scared, and sometimes end up with mismatched parts. We don't have clear guidelines, and state laws haven't caught up. It's a mess. We need standardized labeling and mandatory training.

Ross Ruprecht

November 23, 2025 AT 14:50Why are we even talking about this? Just give people the brand name. If they can't afford it, that's their problem. Pharma's got too many regulations anyway.

Bryson Carroll

November 23, 2025 AT 15:43This whole thing is a joke. The FDA is a bureaucratic joke and the pharmacists are worse. You think a patient can tell the difference between a 0.3mg and 0.5mg injector? Of course not. They just die quietly. And you call that healthcare?

Lisa Lee

November 25, 2025 AT 04:01Canada has this figured out. We don't allow partial substitutions. If the combo isn't approved as a unit, it doesn't go on the shelf. Why can't the US do the same? You guys are behind.

Jennifer Shannon

November 26, 2025 AT 06:42It's like giving someone a single key to a lock that has three tumblers-and then telling them, 'Hey, this key is fine, it's just not the original one.' The lock doesn't care if the key is 'generic'-it only cares if it turns. And when it doesn't? People suffer. We treat medical devices like spare parts, but they're not. They're part of the medicine. The whole thing is a system. And systems fail when you break them into pieces and pretend they're still whole.

Suzan Wanjiru

November 26, 2025 AT 16:22My son has asthma and uses an inhaler combo. We got a generic inhaler with a different spacer last month. He couldn't get the dose in. I had to call the doctor. Turned out the spacer was approved for a different drug. We got the right one after 3 days. This isn't just inconvenient-it's a health risk. Pharmacists need to know what they're dispensing.

Demi-Louise Brown

November 27, 2025 AT 20:48The regulatory framework must evolve. Combination products are not two separate entities. They are one therapeutic unit. Substitution policies must reflect that. Until then, patients are being exposed to unnecessary risk.

Matthew Mahar

November 29, 2025 AT 06:04Wait so you're telling me I can't just swap the drug in my EpiPen with a cheaper one and keep the same injector? But it looks the same!!?? Like why does it matter if the spring is a little different?? I mean come on. I'm not a doctor but I've used these things before and they all seem to work??

John Mackaill

November 30, 2025 AT 01:55There’s a quiet crisis here that no one’s talking about. The people who suffer most aren’t the ones with insurance-they’re the uninsured, the underinsured, the elderly on fixed incomes. They’re the ones who get mismatched generics because it’s the only thing available. And then they’re blamed for not knowing the difference. We need a national standard, not a patchwork of state rules.

Adrian Rios

November 30, 2025 AT 05:58I’ve been in this field for 20 years. I’ve seen the shift from single-drug generics to combination products. And I can tell you this: the system wasn’t built for this. The laws, the reimbursement codes, the pharmacy software-they all assume you’re swapping pills. But when you’re dealing with an injector, a pen, an inhaler, you’re dealing with human interaction, muscle memory, tactile feedback. That’s not a drug. That’s a tool. And tools need to be matched. You wouldn’t put a Toyota engine in a Ferrari body and expect it to run. Why do we do this with medicine?

Casper van Hoof

December 1, 2025 AT 23:33The philosophical underpinning of pharmaceutical substitution is rooted in the reductionist model of medicine-where a molecule is the sole agent of therapeutic effect. But combination products challenge this paradigm. The device is not inert. It is an active participant in the therapeutic outcome. To treat it as separable is to commit a category error of the highest order.

Richard Wöhrl

December 2, 2025 AT 05:29Just checked the FDA’s Orange Book-only 3 out of 24 approved epinephrine auto-injectors are listed as therapeutically equivalent to EpiPen. That’s 12.5%. And only one of those has a generic device AND a generic drug approved as a pair. The rest? You get a generic drug with a branded device (which costs more) or a generic device with no approved drug (which is useless). This isn’t innovation-it’s negligence. Patients deserve better.

Pramod Kumar

December 2, 2025 AT 13:30Back home in India, we’ve got these combo inhalers for asthma-brand and generic-but they’re all tested as one unit. No mixing. No guessing. The patient gets the whole thing, or nothing. Why is America so scared to do the same? We don’t need more paperwork-we need more common sense. A life isn’t a spreadsheet.

Brandy Walley

December 3, 2025 AT 08:04Why do people always act like generics are dangerous? I’ve been using them for years and I’m still alive. You’re all overreacting. The brand names are just trying to keep their monopoly. Wake up.