Why Your Pill’s Color Might Stop Someone From Taking It

Imagine you’ve been prescribed a pill to control your blood pressure. You’ve taken it every day for months. Then one day, your pharmacist hands you a new bottle. The pill looks different-smaller, lighter, maybe even a different shape. You don’t know why. You just know it doesn’t look right. So you stop taking it. This isn’t just about confusion. In many cultures, the appearance of a medicine carries meaning. A pale yellow capsule might signal weakness. A red tablet could mean danger. For someone from a Muslim, Jewish, or Hindu background, a gelatin capsule might contain pork-derived ingredients-something strictly forbidden. And if that’s not clear from the label? They won’t risk it.

Generics make up 70% of all medicines sold in Europe by volume, and nearly the same in the U.S. They’re cheaper, effective, and approved by regulators. But behind those numbers are real people who don’t always trust them. A 2022 FDA survey found that 28% of African American patients believed generics were less effective than brand-name drugs. For non-Hispanic White patients, that number was 15%. Why the gap? It’s not just about misinformation. It’s about history, culture, and how medicine is experienced.

What’s Inside the Pill Matters More Than You Think

Generics must contain the same active ingredient as the brand-name version. That’s the law. But what’s in the rest of the pill? That’s where things get complicated. The inactive ingredients-called excipients-are the fillers, binders, dyes, and coatings. They don’t treat your condition. But they can stop you from taking the medicine.

For example:

- Gelatin capsules are often made from pork or beef. In Islam and Judaism, pork is haram and treif, respectively. Some Muslim and Jewish patients will refuse a medication if they can’t confirm it’s halal or kosher.

- Food dyes like Red 40 or Yellow 5 are common in pills. In some cultures, bright colors are associated with toxicity or spiritual imbalance. A patient might believe a brightly colored tablet is “poisonous” or “too strong.”

- Lactose is used as a filler in many tablets. People with cultural or religious dietary restrictions around dairy, or those with lactose intolerance rooted in ancestry (common in East Asian and African populations), may avoid these pills even if they’re not medically allergic.

- Alcohol-based coatings are used in some liquid or fast-dissolving forms. In Islamic and some Buddhist communities, even trace amounts of alcohol are unacceptable.

A 2023 study in the U.S. found that 63% of pharmacists in urban areas received at least one question per week about excipients from patients concerned about religious or cultural compatibility. Many pharmacists said they spent hours calling manufacturers just to find a version without gelatin or artificial dyes. Sometimes, they had to switch the whole prescription to a liquid form-because no capsule met the patient’s needs.

Appearance Isn’t Just Aesthetic-It’s Belief

People don’t just judge medicine by what’s inside. They judge it by how it looks.

In parts of Latin America, large white pills are seen as “strong” and effective. Small, colorful ones? Those are for children or “weak” conditions. In some African communities, blue pills are associated with sadness or depression. In parts of South Asia, a tablet’s shape can signal whether it’s meant for day or night use.

When a patient switches from a branded pill they’ve used for years to a generic version, even if the active ingredient is identical, the change in color, size, or shape can trigger doubt. They wonder: “Is this the same medicine? Did they cut corners? Is this fake?”

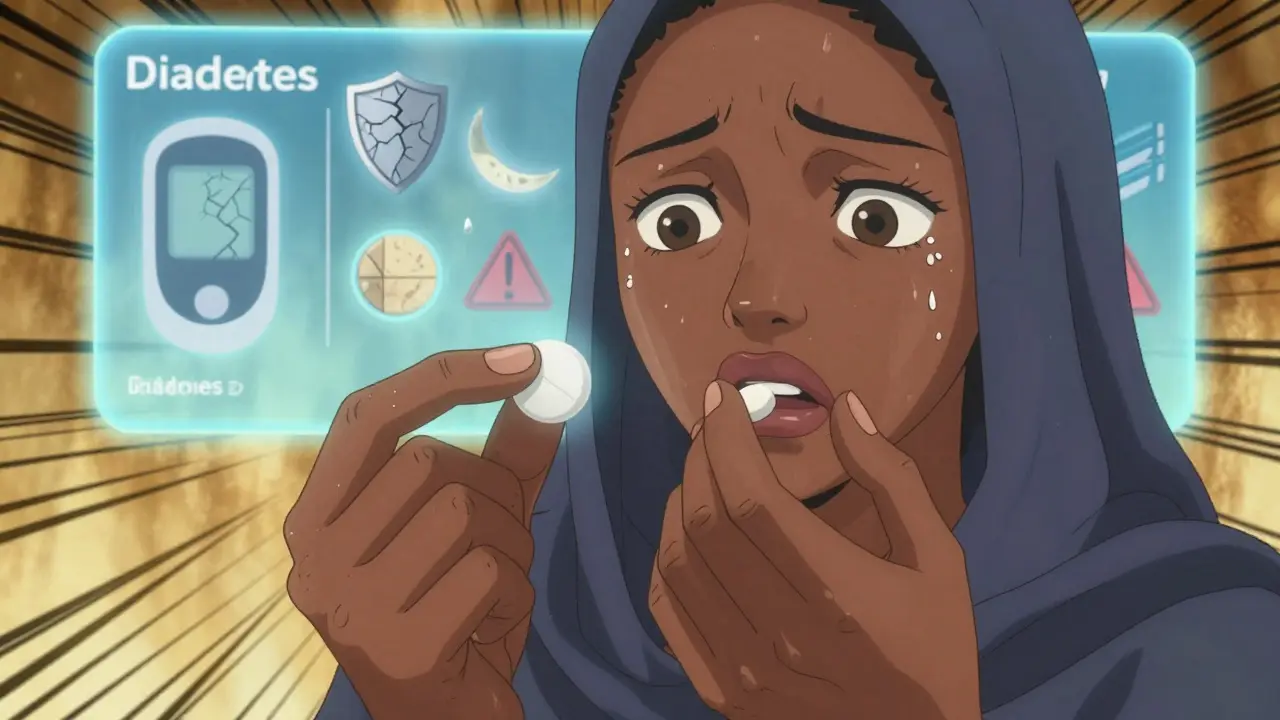

One pharmacist in Melbourne told me about a Somali patient who refused her diabetes medication because the generic version was oval instead of round. She’d been taking the brand-name version for five years. The round shape, to her, meant “real medicine.” The oval one? “Something made for cheap.” She stopped taking it. Her blood sugar soared. She ended up in the hospital.

This isn’t irrational. It’s cultural logic. And it’s ignored far too often in healthcare.

Language, Trust, and the Silent Barrier

Even if the pill is perfectly safe, if the instructions are only in English, many patients won’t understand how to take it. In Australia, nearly 30% of the population speaks a language other than English at home. That’s over 7 million people. But most generic medication leaflets are still printed in English only.

And trust? That’s the biggest hurdle. Historical mistreatment-like the Tuskegee syphilis study in the U.S., or forced sterilizations in Indigenous communities-has left deep scars. When patients from marginalized groups are handed a cheaper generic version without explanation, they don’t always see cost-saving. They see neglect. They see being treated as “less important.”

One study found that Hispanic patients were twice as likely to report feeling “pushed” toward generics by providers who didn’t take time to explain why the switch was safe. That’s not patient-centered care. That’s transactional care.

What’s Being Done-and What’s Not

Some companies are starting to wake up.

In 2023, Teva Pharmaceutical launched a “Cultural Formulation Initiative” to track excipients across all its generic products. By late 2024, they plan to publish halal and kosher certifications for over 150 medications. Sandoz, the generic arm of Novartis, announced a Global Cultural Competence Framework in January 2024, focused on making ingredient transparency standard.

But progress is slow. Only 37% of generic medication inserts in the U.S. list excipients clearly. In the EU, it’s 68%. And only 22% of community pharmacies in the U.S. have any formal training on cultural considerations for generics.

Meanwhile, the market is growing. The U.S. alone has $12.4 billion in unmet pharmaceutical needs among minority populations-mostly in chronic conditions like diabetes, hypertension, and asthma. These are conditions where adherence makes the difference between life and death. Yet, the system still treats culture as an afterthought.

What Pharmacists and Providers Can Do Today

You don’t need a new policy to start making a difference. Here’s what works right now:

- Ask, don’t assume. Instead of saying, “We’re switching you to a generic,” say, “I want to make sure this new pill works for you. Do you have any concerns about what’s in it?”

- Know your excipients. Keep a simple list in your pharmacy: which generics have gelatin? Which are alcohol-free? Which are vegan? Many manufacturers now provide this. You just have to ask for it.

- Use visual aids. Show patients a picture of the branded pill and the generic side by side. Explain the differences in plain language. “This one is smaller, but it has the same medicine inside. The color changed because the company that makes it uses different dyes.”

- Offer alternatives. If a patient refuses a capsule because of gelatin, ask: “Would a tablet or liquid work better?” Not every generic has a halal liquid version-but many do. It just takes a quick call.

- Train your team. Even two hours of cultural awareness training can cut down on refusal rates. Teach staff about halal, kosher, and cultural color meanings. It’s not about becoming an expert. It’s about being respectful.

One pharmacy chain in Sydney started keeping a printed guide in the back room: “Common Religious Concerns & Generic Alternatives.” Within six months, medication adherence among their Muslim and Hindu patients rose by 31%. No new apps. No fancy tech. Just a simple list and a willingness to listen.

The Bigger Picture: Culture Isn’t a Bonus-It’s Core

Generic medications are one of the most powerful tools we have to make healthcare affordable. But affordability means nothing if people won’t take the medicine.

Cultural competence isn’t about political correctness. It’s about effectiveness. It’s about reducing hospitalizations, lowering long-term costs, and saving lives. When you ignore culture, you’re not saving money-you’re creating gaps in care that widen inequality.

The future of generics isn’t just about price. It’s about trust. It’s about dignity. It’s about recognizing that a pill isn’t just chemistry. It’s a symbol. And symbols matter.

Patients don’t need more brochures. They need pharmacists who ask, “Does this work for you?”-and mean it.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do some people refuse generic medications because of the color?

In many cultures, pill color carries symbolic meaning. For example, blue may be linked to sadness in some African communities, while red can signal danger or high potency. In parts of Latin America, large white pills are seen as stronger than small, colorful ones. When a generic pill looks different from the brand-name version a patient is used to, they may believe it’s weaker, fake, or even harmful-even if the active ingredient is identical. These beliefs are deeply rooted and not irrational; they’re shaped by cultural experiences and community knowledge.

Are gelatin capsules always made from pork?

No, but many are. Gelatin in capsules often comes from pigs or cows. For Muslims, pork gelatin is strictly forbidden (haram), and even bovine gelatin must come from animals slaughtered according to halal guidelines to be acceptable. Jewish patients follow kosher rules, which also restrict certain animal sources. Not all gelatin is pork-based, but manufacturers rarely label the source clearly. That’s why patients often ask-and why pharmacists need to know how to find alternatives like cellulose-based capsules.

How can I find out what’s in a generic medication?

Check the product information leaflet, but don’t rely on it alone-many inserts in the U.S. don’t list all excipients. Contact the manufacturer directly; many now provide detailed ingredient lists online. Pharmacists can also use databases like the Australian Medicines Handbook or the U.S. FDA’s Drug Product Database. Some pharmacies now maintain internal lists of halal, kosher, and vegan-friendly generics. If you’re unsure, ask your pharmacist to verify the ingredients before dispensing.

Why do African American and Hispanic patients report higher concerns about generics?

Historical distrust in the medical system plays a big role. Events like the Tuskegee syphilis study and ongoing disparities in care have led many in these communities to view generic prescriptions as a sign of being treated as “second-class.” Studies show that when providers don’t explain why a switch is happening, patients feel dismissed. The perception that generics are “cheap substitutes” is often tied to broader experiences of being underserved. Addressing this requires not just information-but empathy and transparency.

What’s being done to fix this problem?

Some major generic manufacturers like Teva and Sandoz are now tracking excipients and labeling halal/kosher options. The U.S. Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act (FDORA) of 2022 pushed for more attention to social determinants of health, including cultural factors. But progress is uneven. Only 22% of U.S. pharmacies have formal training on cultural considerations. The real solution lies in making ingredient transparency standard, training staff to ask the right questions, and giving patients control over their medication choices-not just their prescriptions.

Alvin Bregman

January 14, 2026 AT 20:32Pharmacists who just hand out generics without asking are doing a disservice. It's not about being politically correct. It's about not letting someone end up in the ER because they were too scared to swallow a blue pill.

Sarah -Jane Vincent

January 14, 2026 AT 22:26Henry Sy

January 16, 2026 AT 04:54And don't even get me started on gelatin. I didn't know half the capsules I've swallowed for years were basically pork rinds in disguise. That's wild. And kinda gross.

Anna Hunger

January 17, 2026 AT 23:22Jason Yan

January 19, 2026 AT 03:45It's like building a Ferrari with a steering wheel that only works if you're from the right town. The science is flawless. The delivery system? Broken. Culture isn't noise-it's the signal. If you ignore how people *feel* about the medicine, you might as well not have made it at all. Adherence isn't about compliance. It's about trust. And trust is built one conversation at a time, not one pill at a time.

shiv singh

January 20, 2026 AT 01:11Robert Way

January 21, 2026 AT 23:49Sarah Triphahn

January 23, 2026 AT 04:19Vicky Zhang

January 24, 2026 AT 02:50That word. Noncompliant. It’s the most cruel word in medicine. It means 'We didn’t listen.'

What if we just asked? What if we kept a list? What if we showed them the old pill and the new pill side by side and said, 'This is the same medicine. The color changed because the company changed. But your life? Still matters.'

That’s all it takes. Just one question. One moment of human connection. That’s what saves lives. Not more pills. More listening.